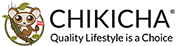

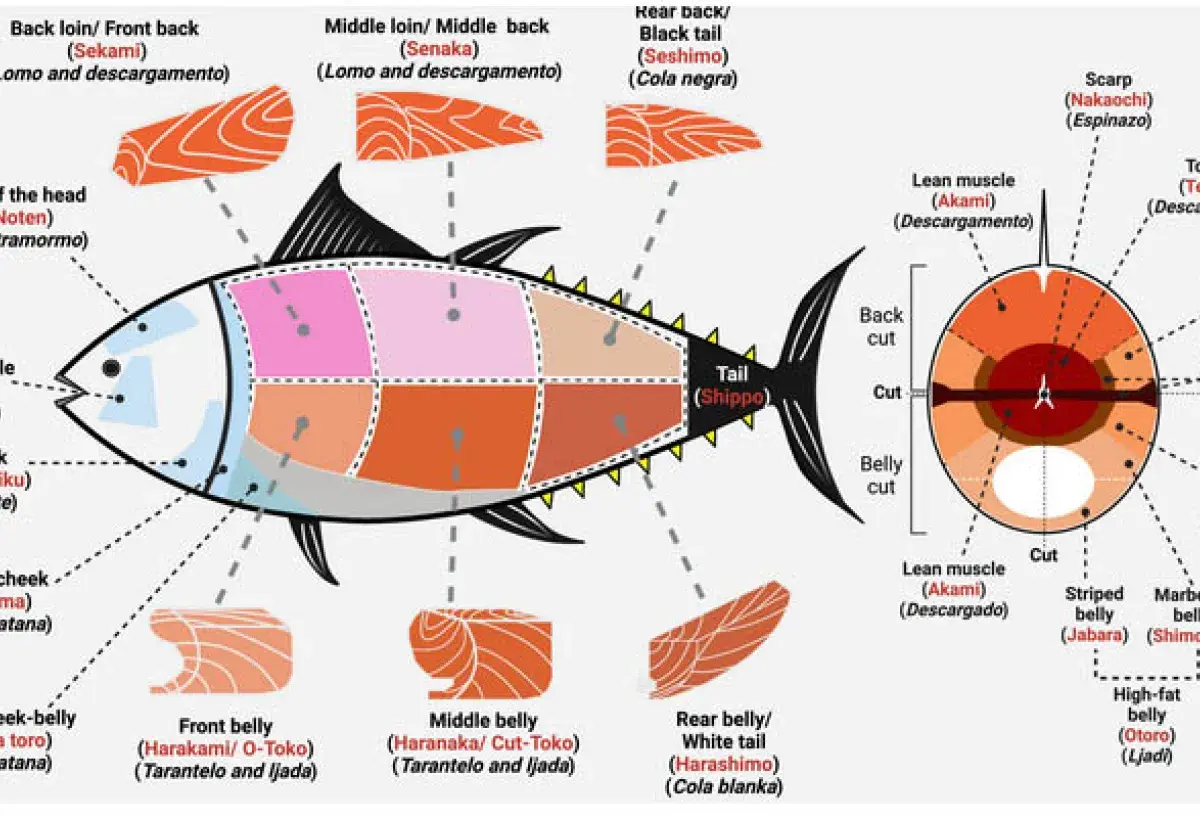

Tuna holds a special place in global cuisine, but nowhere is its importance more refined than in Japanese food culture. What many people casually call tuna is in reality a complex fish with many distinct cuts, each offering its own texture, flavor profile, and culinary purpose. For sushi chefs, understanding these differences is not optional. It is essential knowledge passed down through years of training and experience. Every part of the tuna is respected and utilized with intention, reflecting a philosophy that values balance, craftsmanship, and restraint.

Unlike many other fish, tuna has a large body with muscle groups that vary dramatically depending on location. Some sections are rich with fat and melt gently on the tongue, while others are lean, firm, and bold in flavor. These differences are influenced by how the fish swims, how muscles are used, and how fat is stored for energy. The result is a range of cuts that can feel like entirely different foods despite coming from the same fish.

When you look at a sushi menu, names like otoro, chutoro, and akami are not marketing terms. They describe precise locations on the fish and signal what kind of eating experience you can expect. A skilled chef chooses a specific cut not just for taste, but for temperature, knife technique, and even the season. Some cuts shine when served raw, others benefit from light searing, and some are best enjoyed grilled or prepared as tataki.

For diners, learning these cuts adds depth to the experience. You begin to notice how texture changes from bite to bite and why one piece feels indulgent while another feels clean and powerful. You also gain a deeper appreciation for the fish itself and the skill required to prepare it properly.

We guide you the most common and prized cuts of tuna in a clear and approachable way. Whether you are new to sushi or already a devoted fan, understanding these cuts helps transform a meal into a more meaningful and memorable experience.

Image

1. Otoro

Otoro is widely regarded as the crown jewel of tuna cuts and is often the most luxurious item on a sushi menu. It comes from the fattiest section of the tuna belly, where fat content is at its highest. This concentration of fat gives otoro its signature pale pink color and exceptionally soft texture. When eaten raw, it almost dissolves on the tongue, releasing a rich and buttery flavor that feels indulgent without being overwhelming.

Because of its high fat content, otoro is extremely sensitive to temperature and handling. Skilled chefs keep it cool but not cold, allowing the natural oils to soften just enough before serving. Knife work is also critical, as improper slicing can damage its delicate structure. For this reason, otoro is often reserved for experienced chefs and high end sushi counters.

Otoro is typically served as nigiri or sashimi, with minimal seasoning. A light brush of soy sauce or a small amount of wasabi is enough to enhance its natural sweetness. Too much seasoning would overpower the cut and mask its subtle complexity. Many chefs prefer to serve it near the beginning of a meal so the palate can fully appreciate its richness.

Due to limited supply and high demand, otoro is also one of the most expensive cuts available. Only a small portion of each tuna qualifies as true otoro, making it both rare and prized. When diners choose otoro, they are not just ordering sushi. They are participating in a tradition that celebrates restraint, precision, and the finest qualities of the fish.

Image

2. Chutoro

Chutoro occupies the middle ground between richness and structure, making it a favorite among many sushi lovers. It comes from the tuna belly as well, but closer to the midsection where fat and lean meat exist in balance. This combination gives chutoro a creamy mouthfeel while still retaining a satisfying meaty bite.

Visually, chutoro is deeper in color than otoro, often showing fine marbling that signals its fat content. The texture is soft but resilient, allowing it to hold its shape beautifully whether served as sashimi or nigiri. For many diners, chutoro offers the best of both worlds, delivering indulgence without feeling too heavy.

Chefs often select chutoro for its versatility. It responds well to subtle variations in preparation and can be paired with different types of rice seasoning or light garnishes. A gentle sear is sometimes used to enhance aroma while preserving the interior texture. Even with slight preparation changes, chutoro remains forgiving and consistently enjoyable.

Because chutoro is more abundant than otoro, it is slightly more accessible while still being considered a premium cut. It is often recommended to diners who want to explore fatty tuna without committing fully to the richness of otoro. Over time, many sushi enthusiasts develop a lasting preference for chutoro due to its balance and elegance.

Chutoro tuna sashimi showcasing balanced marbling

Image

3. Akami

Akami represents the purest expression of tuna flavor. Taken from the sides and back of the fish, this cut is lean, deep red, and firm in texture. Unlike belly cuts, akami contains very little fat, allowing the natural taste of the tuna muscle to take center stage.

This cut is often favored by traditionalists who appreciate clean flavors and precise technique. Because akami lacks fat to mask imperfections, freshness is critical. Any decline in quality is immediately noticeable, which is why skilled sourcing and proper storage are essential. When handled correctly, akami delivers a bold yet refined taste that lingers pleasantly.

Akami is commonly served as nigiri or sashimi and pairs beautifully with soy sauce and wasabi. The firm texture provides contrast to softer cuts and helps reset the palate during a sushi meal. Many chefs intentionally place akami between richer pieces to maintain balance throughout the course.

Despite being less expensive than fatty cuts, akami holds immense respect in sushi culture. It showcases the true character of the fish and highlights the chef’s ability to work with simplicity. For many, akami is not a secondary option but a cornerstone of an authentic sushi experience.

Image

4. Kamatoro

Kamatoro is taken from the collar area of the tuna, located just behind the head and near the gills. This part of the fish is constantly in motion, supporting powerful swimming muscles while also storing significant fat. The result is a cut that combines richness with structure, offering an experience that feels both indulgent and substantial. Because only a small amount of kamatoro can be harvested from each tuna, it is considered rare and highly desirable.

What makes kamatoro special is its layered texture. Unlike belly cuts that melt instantly, kamatoro has connective tissue that creates a gentle resistance when bitten. This gives way to juicy, flavorful meat that feels deeply satisfying. The fat content is high, but it is balanced by muscle fibers that provide complexity rather than softness alone.

Kamatoro shines in preparations that apply heat. Light grilling or searing allows the fat to render slowly, enhancing aroma and creating a rich, savory depth. When cooked, the exterior develops a slight crispness while the interior remains moist and tender. Some chefs also serve it as nigiri after a brief torching, which releases its fragrance without fully cooking the meat.

Because of its bold character, kamatoro is often served as a highlight rather than a standard offering. It is a cut that appeals to diners who enjoy rich flavors and textural contrast. For many sushi professionals, kamatoro represents one of the most rewarding parts of the fish to prepare and serve.

Image

5. Sekami and Seshimo

Sekami and seshimo come from the back of the tuna and represent the leaner, more muscular sections of the fish. Sekami is located closer to the head, while seshimo is taken nearer the tail. Although both cuts are low in fat compared to belly sections, their texture and culinary uses differ due to how much each area is used during swimming.

Sekami is relatively softer and finer in grain. The muscles near the head perform controlled movements rather than constant propulsion, resulting in meat that is firm yet approachable. When served raw, sekami offers a clean taste with subtle sweetness and a smooth bite. It is often used for sashimi or nigiri when the fish is exceptionally fresh.

Seshimo, closer to the tail, is firmer and more robust. The tail works hardest during swimming, producing dense muscle fibers that give this cut a pronounced chew. Because of this structure, seshimo is frequently used in cooked preparations such as grilling, pan searing, or simmering. Heat enhances its natural umami while preserving its shape.

Both cuts are important in traditional tuna utilization. They reflect a philosophy that values balance rather than excess fat. Sekami and seshimo are often appreciated by diners who prefer clean flavors and satisfying texture. While they may not carry the same prestige as fatty cuts, they play a crucial role in showcasing the full character of the fish.

Image

6. Harakami and Harashimo

Harakami and harashimo are both taken from the belly of the tuna, but their exact position gives each cut its own personality. Harakami comes from the front portion of the belly closer to the head, while harashimo is taken from the lower belly nearer the tail. This difference in location affects muscle use, fat distribution, and overall texture, which is why sushi chefs treat these cuts differently even though they come from the same general area.

Harakami is typically softer and more delicate. Because it is closer to the head, the muscle fibers are less worked, allowing the fat to spread more evenly throughout the meat. This gives harakami a smooth mouthfeel and a gentle richness that feels luxurious without being overwhelming. It is often served raw as sashimi or nigiri, where its subtle sweetness and tender texture can shine.

Harashimo, on the other hand, has a slightly firmer bite. The tail area of the tuna works harder during swimming, which results in tighter muscle structure. While it still contains healthy fat, that fat is more compact, giving harashimo a satisfying chew. Many chefs enjoy using this cut for light searing or quick grilling, which brings out savory notes while preserving its structure.

Together, harakami and harashimo show how even small changes in anatomy can create meaningful differences in flavor and texture. These cuts are valued for their balance and versatility and are often chosen by diners who want something rich but not as intense as otoro.

Image

7. Hohoniku

Hohoniku is the meat taken from the cheek of the tuna, an area that works constantly as the fish opens and closes its mouth while swimming. This frequent movement gives hohoniku a dense yet tender texture that stands out from other cuts. While it is not traditionally served raw as often as belly or back cuts, it is highly prized for cooked preparations.

When prepared properly, hohoniku becomes incredibly juicy and flavorful. Light searing is one of the most popular methods, creating a caramelized exterior while keeping the inside moist and soft. Tataki style preparation is also common, where the outside is briefly grilled and the inside remains rare. This method highlights the contrast between texture and flavor.

Hohoniku has a deeper, more savory taste compared to lean cuts like akami. It absorbs marinades and seasoning well, making it suitable for ponzu, soy based sauces, or even simple salt and citrus. Despite its richness, it never feels greasy, which makes it appealing to diners who enjoy hearty textures without excessive fat.

This cut reflects the philosophy of using every part of the fish thoughtfully. While it may not be as visually famous as otoro, hohoniku offers a rewarding experience that many sushi professionals quietly admire.

Image

8. Noten

Noten is one of the rarest and most exclusive cuts of tuna, taken from the forehead area near the top of the head. Only a very small amount is found in each fish, which is why noten is rarely seen outside of high end sushi bars or chef tasting menus. Its scarcity alone makes it special, but its texture and flavor are what truly set it apart.

This cut is exceptionally soft and creamy, even more so than many belly cuts. The fat is finely integrated into the meat, creating a smooth and almost custard like mouthfeel. When eaten, noten seems to melt instantly, leaving behind a rich yet surprisingly clean finish. Because of its delicate nature, it is almost always served raw with minimal seasoning.

Chefs treat noten with great care. Temperature control is critical, as even slight changes can affect its texture. It is often sliced thicker than other cuts to showcase its softness and to allow the diner to fully experience its richness. Many chefs consider it a quiet luxury rather than a showy one.

For diners, trying noten is often a memorable moment. It represents the peak of tuna craftsmanship and highlights how even the most unexpected parts of the fish can become something extraordinary when handled with skill and respect.

Image

Understanding the different cuts of tuna transforms sushi from a simple meal into a deeper cultural experience. Each cut represents a specific part of the fish, a particular texture, and a deliberate choice made by the chef. From the indulgent richness of otoro to the clean strength of akami and the rarity of noten, every selection carries intention and respect.

These distinctions also reflect a broader philosophy in Japanese cuisine. Nothing is wasted, and every part of the ingredient has value when treated properly. Learning about these cuts allows diners to appreciate the craftsmanship behind each piece and the journey of the fish from ocean to plate.

For those who love food, this knowledge deepens enjoyment. You begin to notice subtle differences, understand pricing, and make more confident choices at the sushi counter. Over time, preferences develop, and each visit becomes an opportunity to explore something new.

In the end, tuna is not just tuna. It is a story of skill, tradition, and balance, told one cut at a time.